Some links may be affiliate links. We may get paid if you buy something or take an action after clicking one of these.

The moka pot is an important symbol of Italian coffee culture. It is found in 90 percent of Italian households, and is the standard way of making coffee at home in Southern Europe. More than 300 million Bialetti Moka Expresses have been sold since its launch and it has become a design icon. Several art and design museums around the world exhibit the moka pot, including the Design Museum in London and the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. But the moka pot encompasses much more than Art Deco design and strong coffee. The story of the stovetop espresso maker involves the Second Industrial Revolution, Futurism and fascism, colonialism and invasion, war and dictatorship, democratization and a fundamental change in culture.

The moka pot is a stovetop coffeemaker that uses water pressurized by steam to brew strong, espresso-like coffee. The moka pot gets its name from the city of Mocha in Yemen, which was a major exporter of coffee to Europe. It can also be called a caffettiera, macchinetta or stovetop espresso maker. The moka pot is ubiquitous across Southern Europe and has a number of notable makers: Alessi, Cuisinox, Serafino Zani, Bellman, Top Moka, and G.A.T. Though none is more famous than the original, the Moka Express by Bialetti.

The Invention of the Moka Express

The moka pot was invented in 1933 in Crusinallo in northern Piedmont. Alfonso Bialetti returned to Piedmont after working in the French aluminum industry for 10 years. He set up his own workshop to make aluminum household products near his hometown. The most common story for the how Bialetti came up with the Moka Express is that inspiration struck while Alfonso’s wife was doing the laundry. The washing set up was a bucket covered with a cap fitted with a tube. Soapy water in the bucket was brought to a boil, building pressure and pushing the water up through the tube to disperse over the laundry. With the help of Luigi De Ponti, Bialetti eventually developed a brewing device that worked in essentially the same way.

How a Moka Pot Works

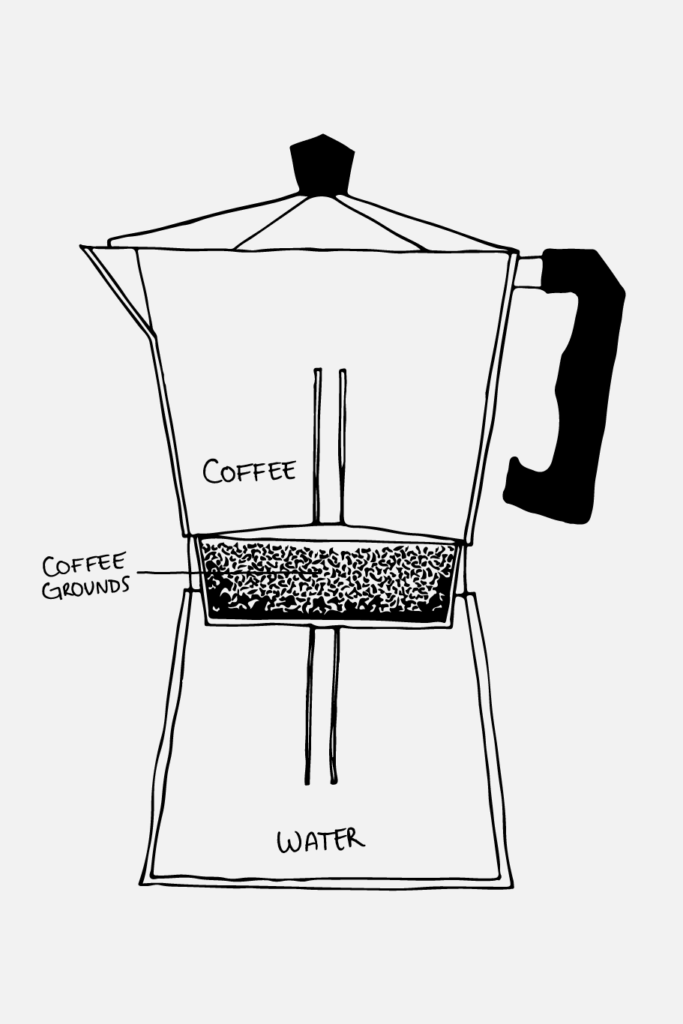

Bialetti’s Moka Express is an octagonal device made of aluminum with bakelite handles. The device has three major sections: a lower chamber, a metal filter, and an upper collection chamber. To brew, the lower chamber is filled with water and then the metal filter is set onto the lower chamber and filled with coffee grounds. The upper chamber is screwed on and the whole moka pot is placed on the stove. When the water boils, the steam increases the pressure in the lower chamber and forces the water through the coffee grounds in the filter. The coffee then condenses and collects in the upper chamber. When the lower chamber is almost empty, pockets of water vapor are also forced through the filter into the upper chamber, creating the characteristic gurgling noises.

But Is It Really Espresso?

While the coffee produced by a moka pot is strong and sometimes even produces a crema, it is not the same as espresso as we know it today. A moka pot brews under pressure and creates a coffee with a similar extraction ratio to espresso. The standard pressure for modern espresso machines is at least 9 bars, whereas a moka pot extracts coffee at a pressure of 1.5 bars. A moka pot also reaches higher temperatures, about 100°C whereas an espresso machine generally brews at 92-96°C. But the rich, concentrated coffee is not a bad home alternative, if you follow a few guidelines for better brewing. In fact, the mechanics of a moka pot are similar to the workings of the first steam-driven espresso machines.

The espresso machine in Italian bars at the time of the moka pot’s invention was La Pavoni. La Pavoni were impressive and ornamental machines that bars could show off to the patrons. To brew, the entire espresso machine is placed over a flame. Inside the machine, a tube leads from the bottom compartment to a puck of ground coffee. As the water boils, the pressure builds and forces steam and hot water up through the tube and the ground coffee. La Pavoni was a large, commercial espresso machine meant for bars to be able to quickly serve coffee on demand, expressly for each customer. They were too expensive and cumbersome for use in all but the wealthiest homes.

Bringing the Espresso Bar Home

Ever since coffee arrived in Europe, it had been a communal activity. Coffee was consumed in public spaces by the elite. Coffeehouses were places to share the latest news, debate on politics, poetry and literature, and to do business. In fact, many modern financial services firms in London started originally as coffee shops, including stock exchanges and Lloyd’s. With the Second Industrial Revolution, cafés needed to cater to workers stopping in for coffee on their way to and from work. Espresso machines were developed to solve a commercial problem: quickly serving customers a coffee on demand. During the second half of the nineteenth century though, coffee was beginning to speed up and to enter private homes.

In Italy, two devices were commonly used to make coffee at home. The Napoletana and the Milanese. A Napoletana was a reversible pot. The first chamber is filled with water and set on the flame, and once the water boils the entire device is flipped so the hot water trickles through the coffee grounds and is collected in another chamber. With a Milanese, water is boiled until is passes through ground coffee in a strainer at the top of the device. The coffee made by these devices did not brew by pressure like espresso machines and made a very different style of coffee.

Art Deco Design and Futurism

Alfonso Bialetti’s Moka Express, therefore, was not the first foray into home-brewed coffee. But, it was the first device capable of making at home the same restaurant and bar style of coffee of the time. His design deliberately attempted to fit the workings of La Pavoni espresso machines into a stovetop device like the Napoletana. Once he had a working model, he cheekily created a design that echoed the already popular silver coffee services by high-class brands like Hénin and Puiforcat. In so doing, he preserved design elements of Futurism and Art Deco into a device still widely used today.

Futurism was an art movement popular in Italy in the early 20th century that celebrated technology, power and modernity. The movement emphasized the birth of new ideas through the destruction of older forms of culture. Followers of Futurism had an insatiable desire for modernity that relished the beauty of the machine, speed, violence and transformation. Futurism was born with the publication in 1909 of the “Manifesto of Futurism” by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the self-proclaimed “caffeine of Europe.” Marinetti sought to destructively free Europe from its past to welcome a modern, industrial-era where technology triumphs over nature.

The Rise of Italian Fascism and the Marriage of Coffee and Aluminum

Futurism arose at an interesting period for Italy: shortly before World War I. Futurists enthusiastically enlisted. As expressed in Marinetti’s manifesto, “we will glorify war—the world’s only hygiene—militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for women.” After World War I, Italian Futurism heavily influenced the rise of Italian Fascism. Marinetti founded the Futurist Political Party which quickly merged with the Italian Fasci of Combat, the fascist party founded by Mussolini. In fact, in 1919, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti authored the “Fascist Manifesto,” the declaration of the political stance of the new party. In 1922, King Victor Emmanuel III appointed Mussolini as prime minister. He led Italy constitutionally until 1925, when he established a dictatorship.

In the 1930’s, aspects of futurism and Mussolini’s fascism created the perfect context for the invention of the moka pot. Italy had a rich supply of bauxite and leucite, used for the production of aluminum. Futurism’s reverence for machines, technology, and metallic modernity combined with fascist nationalism meant that aluminum would become the national metal of Italy. Mussolini imposed an embargo on stainless steel to compel taking advantage of its domestic aluminum ore.

Caffeine was not only emphasized in Futurism’s movement and progress, but it was also linked to Mussolini’s foreign policy. Italy invaded Ethiopia in 1935 pushing the Abyssinia Crisis to culminate in the Second Italo-Abyssinian War. Ethiopia lost its independence in 1936 and became Italian Ethiopia, part of Italian East Africa. As a result, the League of Nations listed Italy as an aggressor and imposed sanctions. Italian East Africa became an important source of coffee for Italy, as well as Brazil which ignored the League of Nations sanctions and continued to export coffee to Italy. Thus, Mussolini kindled the Italian marriage between coffee and aluminum.

Renato Bialetti and the Rise of the Moka Pot

The moka pot wasn’t immediately popular though. Alfonso Bialetti initially sold the Moka Express at public markets around the Piedmont region or sold to retailers from his workshop and it was only one of many products that he produced. He never attempted to industrialize the process or scale nationally, let alone internationally. In the time between inventing the Moka Express and the break out of World War II, Bialetti only produced about 70,000 moka pots. During World War II, aluminum was mostly used for war materials and unavailable for household products. Imports mostly discontinued which also made coffee difficult to find. Bialetti closed down his workshop in the course of the war.

Alfonso’s son Renato had been held at a German prisoner of war camp, but made it back home in 1946 to take over his father’s shop. Renato is mainly responsible for the Moka Express’s success. After World War II, there was a surplus of factories and skilled manufacturers. Renato decided to focus solely on the Moka Express and began mass production.

Italy’s post-war economy did especially well and the middle class was growing. Renato became a skilled marketer, presenting the Moka Express as a design object and executing extensive advertising campaigns. Renato commissioned the famous Omino coi Baffi, or “the little mustachioed man” from Paul Campani in the early 1950s. The Omino coi Baffi, a caricature of Renato’s father, Alfonso, was plastered over every billboard during the trade fair in Milan, along with the slogan “in casa un espresso come al bar.” “An espresso at home just like at the bar.” One year at the entrance to the fair, Bialetti displayed a giant Moka pot sculpture (over 6m) pouring coffee into a cup.

A product heavily influenced by Futurism and made possible by Fascist policies went on to make espresso at home accessible to any income, democratizing a luxury experience. Italian coffee shifted from being almost exclusively a social drink sipped at bars to an intimate ritual in private homes. A quotidian device, embedded in so many people’s daily routines, is actually a rich brew of major historic movements.

How to Brew in a Moka Pot

Grind coffee beans finely, like fine sea salt. Do not use an espresso grind, it will make the coffee too bitter.

Boil water in a kettle and fill the lower chamber to just below the valve.

Using already boiled water reduces the bitterness as the moka pot spends less time on the heat and the ground coffee doesn’t get as hot. The valve is a safety measure that prevents too much pressure building up. Don’t cover it.

Put the metal filter in place and fill the basket with the ground coffee. Level the top gently. Don’t overfill and compact the coffee.

Screw on the upper chamber.

Put the moka pot on the stove on low to medium heat and leave the lid open.

Coffee will slowly rise through to the upper chamber. As soon as you hear the gurgling noise, take the moka pot off the stove and run the base of the pot under cold running water.

The gurgling happens when steam begins to rise through the coffee bed, which will lead to a bitter cup. Running the bottom chamber under cold water quickly stops the brewing process by lowering the temperature, condensing the steam and lowering the pressure in the pot.

the Sunday Baker is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

I have two old and unique Moka Pots. Do you know where I could find info on them? Are there collectors out there?

Hi Charles, that’s so cool! I don’t know too much about finding info on antique moka pots, but I did find a recommendation about an expert named Lucio del Piccolo. I’d check out the following sites Home Barista, Caffettiere e macchine da caffè, and Collezione Enrico Maltoni.